Forged in Friendship

By Molly K. Painter

The scene was set and Bert and Ellen Witt were ready to host their 50th wedding anniversary celebration in 1990. They had invited an intimate group of close family and friends to help them celebrate. An artist friend and his wife had come the day before to the Witt’s home in Los Angeles, California. As the artist handed Ellen a charcoal drawing, Ellen was elated and took pause at the unique gift.

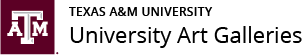

The artist was Allan Houser, one of the world’s most renowned Native American sculptors and Modernists of the 20th century. Despite his artistic fame, the Witt’s affection for the artist came from a lasting and enduring friendship they shared with him and his wife Anne (Anna Marie). Their introduction came many years before, when the Witt’s stumbled upon Houser’s work in Arizona in 1982.

Upon entering the courtyard of The Gallery Wall in Scottsdale, Bert and Ellen immediately stopped in their tracks, sighting a bronze mother-and-child statue on a pedestal called “Sounds of the Night.”

“The face of the mother was as finely chiseled as it could possibly be,” Bert wrote in a document detailing his friendship with Houser. “The rest of her solid, substantial body, seated with one foot tucked under her, was covered by a blanket. Out of the blanket peered only the cherubic face of her sleeping baby.

“Ellen and I looked at each other, joyfully, helplessly. We knew we were hooked.”

A relative of Geronimo, artist Allan Houser’s familial roots ran deep and colored his work; in 1914, he was the first Chiricahua Apache baby born out of captivity after the U.S. government’s decades-long internment of his family’s tribe as prisoners of war. His path led him from the Oklahoma family farm where he grew up to the Santa Fe Indian School in New Mexico. Honoring his artistic talents while also supporting his young family, Houser worked in roles as painter, sculptor, teacher, illustrator, construction worker, and even a Golden Gloves boxing champion.

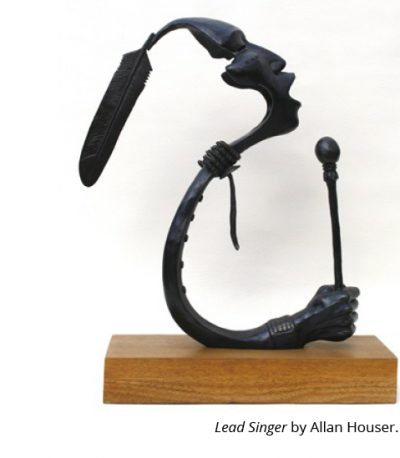

As the Witts left the courtyard and entered the doors of the Scottsdale gallery, they were further entranced by the dozens of Houser sculptures depicting Native American subjects – a woman telling a child her father would be singing at an upcoming ceremonial event, entitled “Your Father Will Sing,” and what appeared to be a partial face, throat, and hand, grasping a drum stick playing an unseen drum, called “Lead Singer.”

“The anatomy was all wrong. The sculpture was exactly right,” Bert wrote, referencing the abstract lead singer bronze. “I realized Mr. Houser had sculpted only what the ceremonial firelight had lit up. Brilliant!”

Bert and Ellen purchased “Sounds of the Night,” the courtyard bronze that initially caught their attention, on the spot. But Bert had a secret plan for the other two “singing” sculptures – he would arrange to take out his retirement savings from his textile company in a lump sum and surprise Ellen with them at Christmastime.

Their newfound discoveries were indicative of Houser’s golden, retirement years. While he had earned early success and had already won many awards, Houser’s most recognizable modern stylings were chiseled out later in life. Melding his boyhood memories of Apache life on the farm with abstract figures evoking the Modernist movement, Houser carved out his artistic legacy in bronze, marble, and stone.

The Witts found themselves later that year in New Mexico in connection with the non-profit group Futures for Children, an organization they volunteered with in California. This trip led to an arranged first meeting with Houser and his wife Anne in Santa Fe. They met at the landmark restaurant, The Pink Adobe, and Bert would later write on the La Fonda Hotel stationery where they were staying: “Houser wore a flowered western shirt, plain tan slacks, a simple turquoise choker and an exquisite, simple, very old, wide wristlet of turquoise and silver. Houser wears glasses. His general appearance is that of a quiet, kind grandfather.”

Writer and biographer W. Jackson Rushing III notes that Houser was sensitive and soft spoken, translating into “a tender lyricism and lithic powers in his sculptures.”

“He was legendary for being accessible and generous with his time,” Rushing wrote, “both willing and able to articulate his aesthetic vision to patrons, curators, critics, and journalists.”

The Housers and the Witts quickly became fast friends and the dinner and conversation led to a visit the next morning at Houser’s studio in the desert outside of Santa Fe.

The couples’ friendship would continue to grow as the Witts would return to the Houser’s home and studio many times over the years, seeing works transform from an idea or a sketch to a finished work. They would attend most of the artist’s openings and rarely left without a new piece of art to take home. Birthdays were celebrated together, along with vacations, picnics, and drives through the New Mexico desert. The Housers even volunteered their time and travels to assisting the Witts in their work with Futures for Children. The two couples shared many things in common, and they truly liked each other, as Bert noted in his accounting of their times together.

“The Housers knew that the Witts didn’t want a single thing from them except friendship. We didn’t trade on their name; we didn’t bask in their glory; we didn’t abuse their secrets,” he wrote. “The Witts knew that the Housers weren’t being friendly because we were purchasers of Allan’s sculpture. That opened the door originally, but the friendship prospered most in the years after we could acquire no more and stopped buying.”

The anniversary celebration had come to a close and the Witts said their goodbyes to the guests who had come to share in their joy. They quickly pulled out the conceptual charcoal drawing from Houser, and Bert remarked to Ellen that just like their friendship with the Housers, this gift was something extra special – for the sculptor to gift them with an original drawing meant he had not only given them a piece of his vision, but he had gifted them with a piece of himself, of his heart.

While Allan Houser’s drawings and sculptures continue to live on at his gallery and a sculpture park in Santa Fe, New Mexico, his earthly body ultimately succumbed to cancer in 1994.

“We had lost one whom we considered a close and dear friend,” Bert wrote. “It was hard to pick up a handful of dirt and drop it on the coffin when our turn came.”

The Witt’s son, Peter, a former department head in the Texas A&M University Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences Department, and his wife, Joyce Nies, a former agent in Nutrition and Food Safety with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, have donated a portion of their Native American and Inuit art collection, including two original works by Houser inherited from Peter’s parents, in memory of Bert and Ellen Witt to the Texas A&M University Art Galleries.

To learn how you can support the Texas A&M University Art Galleries and their Native American collection through monetary or artwork donations, contact Reagan Chessher at the Texas A&M Foundation.